A reply to key comments on our rebound article and blog post

______________________________________________________________________

The following is a joint blog post by Danny Cullenward and Jonathan Koomey

______________________________________________________________________

Last Monday (January 4th, 2016), we published a postsummarizing the implications of our critique of Harry Saunders’ article on rebound effects in the US economy. We have since received thoughtful comments from Dr. Saunders (a Senior Fellow at the Breakthrough Institute (BTI)), Jesse Jenkins (a PhD student at MIT and lead author of the 2011 Breakthrough Institute rebound report that relied on Saunders’ article), and Steve Sorrell (Professor at the University of Sussex and a BTI Senior Fellow*).

Here, we address the main objections our critics have raised. We pay special attention to Professor Sorrell’s comments because they have been endorsed by Mr. Jenkins, BTI Chairman Ted Nordhaus, and BTI co-founder and Senior Fellow Michael Shellenberger.

To begin, we note that none of our critics have disputed our core finding: that Dr. Saunders’ analysis relied on national average energy prices, not the sector-specific prices he claimed his data represented. In addition, Dr. Saunders used average annual price data, whereas economists generally prefer marginal prices to properly isolate the rebound effect from unrelated behavioral and energy market-induced changes.

Given the nearly five years it took to prompt a discussion about Dr. Saunders’ evidence, including long conversations over email and in person, the silence on this point is notable. Nevertheless, we take it as a sign that all sides agree on these critical observations, which (as we pointed out in our response paper) have always been confirmable both directly in the data in question and its documentation. There are many more problems to work through, of course, but this is a productive start.

Having at least acknowledged some deficiency in Dr. Saunders’ analysis, then, our critics either implicitly distance their policy positions on the rebound effect from Dr. Saunders’ article and/or defend the econometric analysis of energy price data we have shown to be woefully inadequate. Below, we review these arguments and offer some responses.

Argument 1: Don’t Let the Perfect Be the Enemy of the Good

Scientists don’t always have perfect data and sometimes they need to make assumptions about missing information. That’s fine when done explicitly and accompanied by uncertainty analysis to illuminate how the analyst’s assumptions affect the results. The problem here isn’t that there’s a missing piece of information, however, but rather that the entire data set, because of its limitations, cannot support credible investigation of the research question.

In a comment on earlier post, Professor Sorrell praises Dr. Saunders’ analysis for its nuance, asks what would happen if we had re-run his model with better data, and wonders why we didn’t report any such results:

A commendable feature of [Dr. Saunders’] paper is the 3 pages devoted to listing ‘cautions and limitations’. The potential inaccuracies in energy price data simply adds one point to this list. In the absence of any empirical tests (why not repeat the analysis with the revised data??), you have not demonstrated that the data inaccuracies lead to any systematic bias in the rebound estimates, or that the bias is necessarily upwards rather than downwards. Hence, it is misleading to conclude that the results are 'wholly without support’.

Our response: Professor Sorrell addresses only one of the two major errors we identified in Dr. Saunders’ analysis (data quality). In ignoring the other (data structure), he calls for the impossible.

First, let’s review the structural issue. Again, Dr. Saunders’ data report national average energy prices, not the sector-specific prices he claimed to be using. The idea that this fundamental misunderstanding can be corrected by adding another bullet point to a list of caveats would be an audacious remedy, as we pointed out previously:

Lest this seem like a petty academic grievance, it’s as though Dr. Saunders set out to study the performance of individual NFL quarterbacks when their teams are behind in the third quarter of play, but did so using league-wide quarterback averages across entire games—not third-quarter statistics for each player. If that doesn’t sound credible to sports fans, trust us, it’s an even bigger problem when you’re talking about the last fifty years of U.S. economic history.

If Professor Sorrell only meant to suggest that the data qualityproblems could be addressed with a new caveat, he nevertheless glosses over the structural issues. On their own, the structural issues offer sufficient reason to question Dr. Saunders’ results.

Let us assume that Professor Sorrell is concerned more with the data quality issues we raise. As we discuss at great length in our response article and its supplemental information—have our critics yet digested these documents?—one cannot actually trace the primary source of Dr. Saunders’ data. That should be reason enough to take stock of the reasonableness of their use. If additional reasons are desired, the data documentation includes more than a few heroic (and largely arbitrary) assumptions necessary to fill in gaps in the historical record; a heavily footnoted research trail in our supplemental information provides a map for the interested reader.

Having dug into the details, our view is that one simply can’t treat these energy data as precise for the purposes of econometric modeling of the rebound effect.

Consistent with Professor Sorrell’s suggestion, we would have been be happy to apply Dr. Saunders’ model to a more robust data series, except that (as we once again pointed out in our article) no such data exist: Dr. Saunders’ model requires data at a level of detail that simply is not available in the United States. Reconstructing the data from primary sources or addressing their current validity in light of the lack of primary data sources would take a PhD dissertation, not an extra footnote—if it could even be done at all with the available primary sources, which remains an open question.

To recap, Dr. Saunders mistakenly employed national average energy prices while believing his model was processing sector-specific price data. Moreover, he treated his data as though they were precise, when a closer examination reveals their construction involved several unfounded assumptions and oversimplifications that should undermine confidence in any subsequent econometric analysis. That one cannot trace the data back to its primary sources adds an additional layer of concern for anyone with high standards for data quality. As a result, the data structure and data quality issues are each fundamental problems with the published analysis, not missing entries on a long list of caveats.

Hence, we concluded that Dr. Saunders’ results are wholly without support because his data do not match his model specifications and because the available primary data cannot address the research question at hand.

Argument #2: It’s All About the Variation

Dr. Saunders makes the most direct defense of his paper, arguing that his model accurately captures the essence of the rebound effect despite imperfections in the data:

Not clear that the absolute energy price matters much. Variation is fundamental driver. Historical energy price sets used for econometrics vary by nearly an order of magnitude over the time series, sufficient to tease out production behavior over a wide range of input prices.

The premise here is that other models are successfully calibrated using data featuring levels of variation that are comparable to those found in Dr. Saunders’ own data. Dr. Saunders therefore suggests that his data are sufficient to calibrate the model in a way that allows it to achieve statistical validity.

With respect, we’re not comfortable with the idea that using incorrect absolute energy prices is immaterial to the validity of one’s results. Assuming, however, that for some particular statistical model the variation in energy prices is the only key input variable, Dr. Saunders still hasn’t made a reasonable defense. A data set might contain sufficient variation in order to be sure that a model is exposed to a wide range of input data that covers the relevant analytical space in mathematical terms. But nothing about that statement indicates that the reported variation accurately reflects the actual economic choices the data are supposed to measure.

In other words, there may be sufficient variation in Dr. Saunders’ data to ensure that the model can be calibrated using these data, but that doesn’t say anything about the accuracy of either the data or results. (Or more bluntly: variable garbage in, well-calibrated garbage out.)

We are reluctant to re-hash all of our data concerns here. After all, that’s why we wrote a paper and included a lengthy technical appendix, the substance of which none of our critics has yet addressed. But for the sake of argument, we’ll review two issues here to hammer the point home.

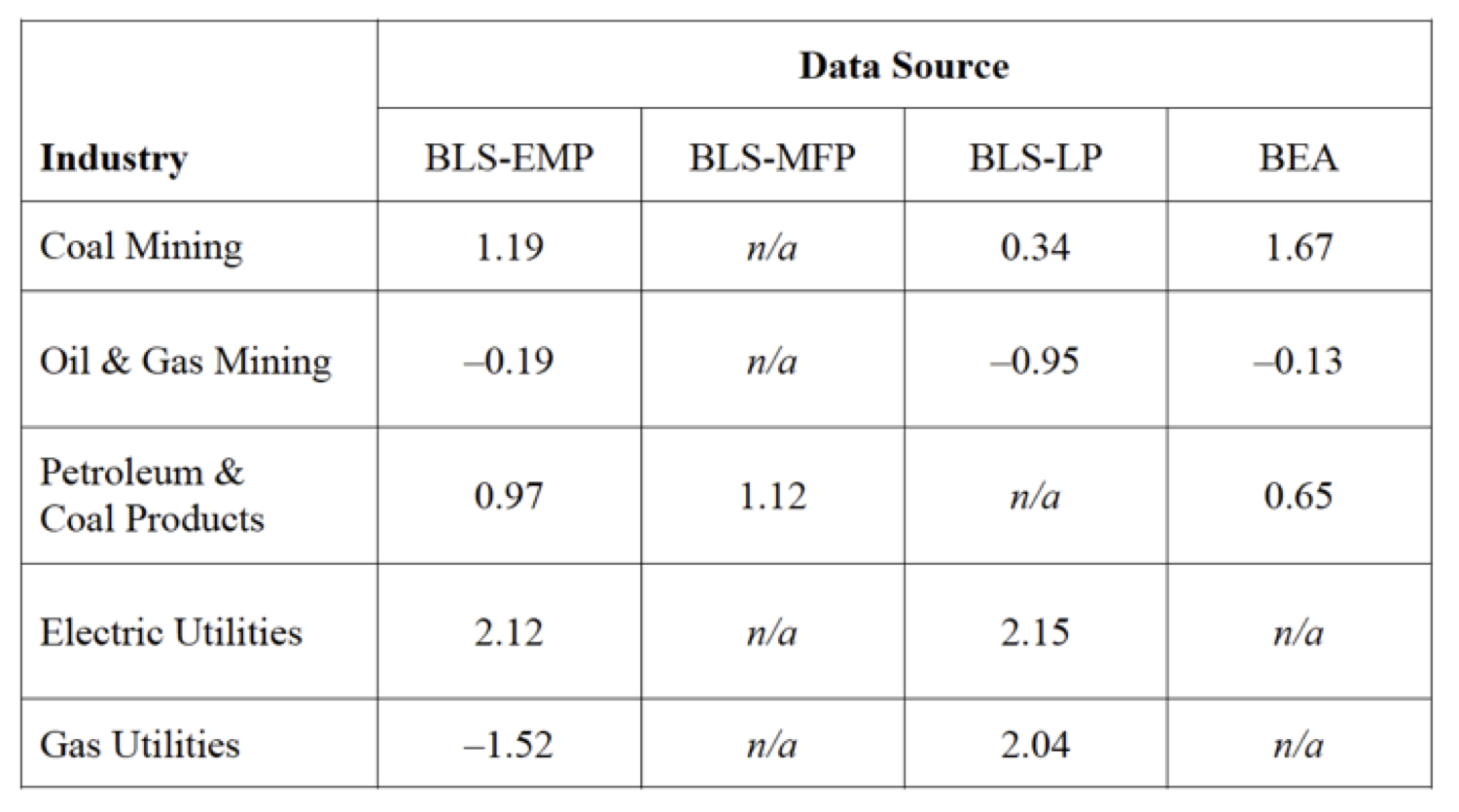

First, in one of the references in Dr. Saunders’ paper (Jorgenson et al., 2005),[1]the authors of Dr. Saunders’ data describe how the selection of different primary data sources would change key parameters in the data set Dr. Saunders used. As we discuss in our response article, the KLEM data are the product of input-output (I–O) tables, which show the annual expenditure flow between each of 35 industries in the accounting system Dr. Saunders employed. In Table 1 below (see Table SI-1 in our appendix), we illustrate how four different primary data sources from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) report different gross output growth rate statistics for each of the five energy sectors in the KLEM data series (i.e., the “E”). (Professor Jorgenson ultimately selected the BLS-EMP series, though as we discuss in our article’s appendix, BLS no longer publishes these data.)

As Table 1 shows, there is a huge amount of variation across primary data sources—not the good kind, unfortunately, but the type that illustrates how uncertain the selected data are. But the story is even more problematic than that. These statistics are for output growth rates for each of the sectors, not the I–O tables at the core of Professor Jorgenson’s (and hence, Dr. Saunders’) data. Gross output by sector is much easier to estimate than are I–O tables because there are gross outputs for each of n sectors (n=35) while an I–O table is a matrix with n2 entries (35 x 35 = 1225). The best statistical estimates of I–O tables are made in the so-called benchmark economic surveys that BEA conducts once every five years; data for the years in between are extrapolated, not directly observed. So it’s very likely that there is even more variation (and therefore less precision) across primary data sources that attempt to estimate the full I–O matrix.

Table 1: Comparison of average annual growth in gross output by sector and data source (average % growth per year, 1987-2000)

As a final point, Table 1 reports the five industries constituting the “E” in the KLEM data series and in Dr. Saunders’ model; each is represented by a single national average price. Yet most energy economists would not recognize each of the five “E” economic categories as representative of real energy markets or energy prices: for example, our earlier post showed how electric utility rates vary widely by sector and geography, and are not readily related to a single national average. (Again, these are national averages, not marginal prices; marginal prices are the fundamental driver of rebound effects in standard microeconomic theory and differ substantially from average prices in the electric sector.)

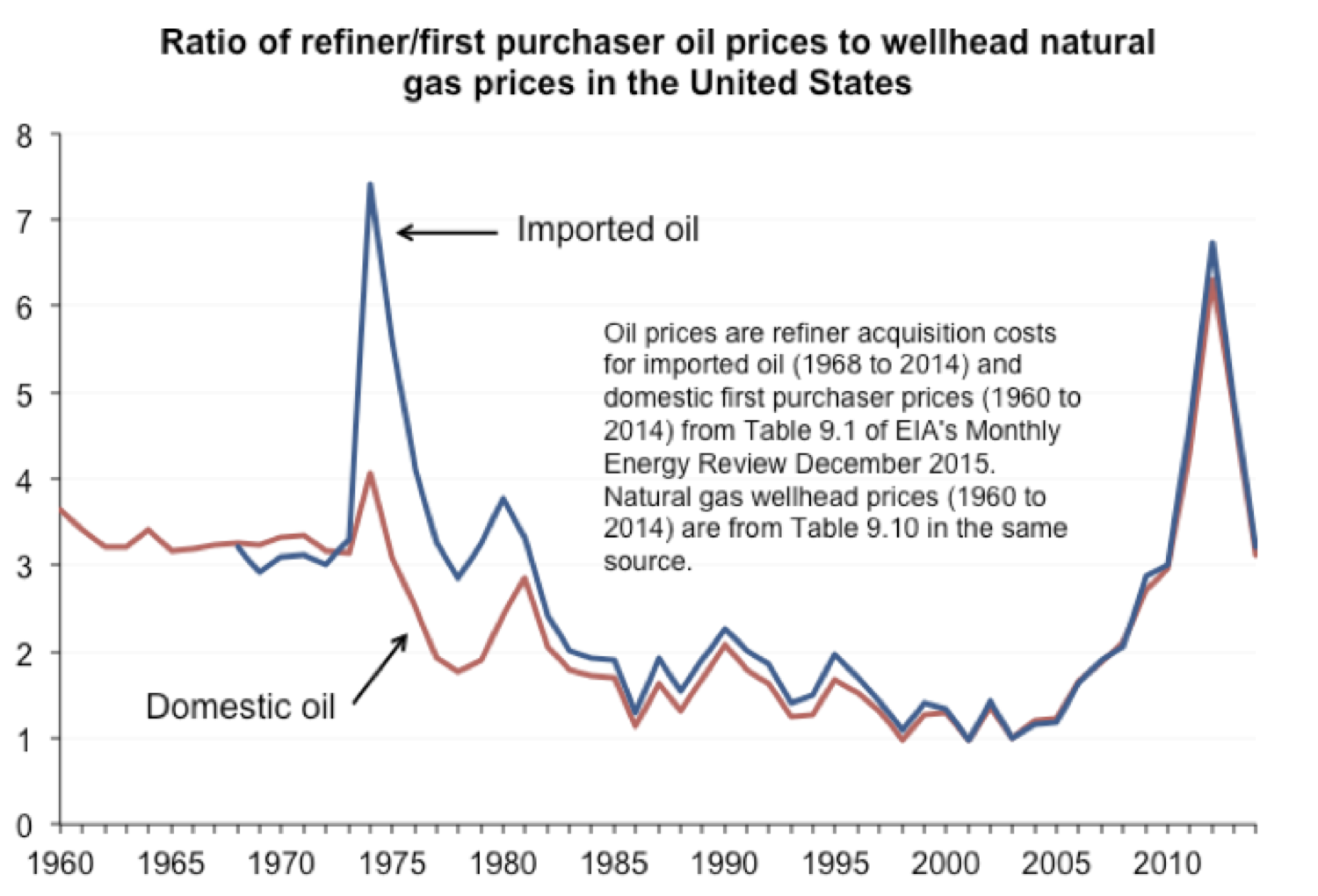

As an additional example, we’d point to the “Oil & Gas Mining” sector, which combines all domestic oil and gas production. In Dr. Saunders’ data, there is a single price signal for consumption of domestic oil and natural gas, two fossil fuel resources that have in reality experienced great and uneven changes over the last 50 years. Below, we use Energy Information Administration data to plot the ratio of oil prices to wellhead natural gas prices as a simple visual measure of how unreasonable that assumption is, given that (1) natural gas and oil often compete with each other and (2) relative prices matter a great deal in determining such choices.[2]

Figure 1: Ratio of oil to natural gas prices

A quick review of the figure shows that oil and natural gas prices do not vary in tandem. Indeed, there are two periods of significant relative price shocks in which oil prices spiked relative to gas prices. Most famously, this occurred during the mid-1970s oil crisis, during which time domestic price controls led to a significant divergence between the price of domestic and imported crude oil. Thus, if a firm had a long-term contract with a domestic oil producer, it faced a substantially different price compared to a competitor who had to buy imports from the global crude market. Subsequently, price controls were lifted and the difference between domestic and imported prices diminished.[3]

As the figure illustrates, nothing about economic history suggests that a composite oil and gas production sector (with one average price series representing both resources) could accurately measure the variation in relative gas and oil prices that actual economic actors have faced since 1960. Yet this assumption is necessary for the I–O structure of Dr. Saunders’ data to function and is therefore an embedded error in his assessment of sector-level rebound effects.

Argument #3: Everyone is Doing It

Another argument suggests that the problems we identify in Dr. Saunders’ article are no more significant than is the norm in acceptable scholarship in this area of research.

Here is Professor Sorrell again:

Your critique over potential inaccuracies in the energy price data could probably be extended to the capital, labour and materials data - where measurement problems are greater. But you would need to be acknowledged [sic] that these issues are not unique to Saunders paper, or to Jorgensen’s huge body of work, but are generic to the majority of work in this area.

Dr. Saunders echoed this view as well:

Your critique would extend to all of Dale Jorgenson’s multiple peer-reviewed energy studies. Doubtful he would see a serious problem.

Our response: The energy data (which were prepared by Harvard Professor Dale Jorgenson) are indeed problematic, no matter the prestige of their users or developers. Dr. Saunders’ initial misunderstanding about the structure of these data is entirely unrelated to Professor Jorgenson’s work and sufficiently problematic on its own, but our concerns about the underlying quality of the data do apply more broadly.

As for the comparison to the other KLEM data categories (capital [K], labor [L], materials [M]), we didn’t do the heavy lifting and so have been careful not to comment on this issue in the article or in our earlier blog post. As outsiders to the field of macroeconomic accounting, our presumption was that experts are engaged in detailed discussions of the uncertainties inherent in these estimates and are attempting to address the associated uncertainties in an academically rigorous way.

However, if Professor Sorrell is correct to suggest that the data for capital, labor, and inter-industry transactions are as bad as they are for energy but are not subject to comprehensive uncertainty analysis, then that should give us all pause. Certainly we can’t imagine using problematic data in our own work. Does anyone think the standard should be lower?

Argument #4: Saunders as Strawman?

Separately, Mr. Jenkins and Mr. Nordhaus also addressed our criticism of the Breakthrough Institute report, which heavily featured Dr. Saunders’ results. They argue that it isn’t fair to impugn the whole BTI report based on issues with, as Mr. Jenkins put it, one of over a hundred references. Mr. Nordhaus even went so far as to say that our criticisms of Saunders’ paper amount to “cherry picking” and “knocking down strawmen” when it comes to BTI’s view of the rebound effect.

We are disappointed in these responses for two reasons.

First, as we documented in our original blog post, Dr. Saunders’ article was the very centerpiece of the 2011 BTI report. Indeed, it provided the sole empirical claim to novelty compared to earlier reviews of rebound by Professor Sorrell, the late Lee Schipper, and others. The BTI authors referred to the Saunders analysis again and again, as we described in our previous post:

In most literature reviews, individual paper results are reported in tables or figures and, where the insights or methods are particularly important, briefly discussed in the main text. In contrast, the Breakthrough Report cites Dr. Saunders’ paper 25 times across 17 pages, with several full-page discussions and a detailed reproduction of its complete results. No other citation received anywhere near this level of attention.

Thus, the notion that this is just one reference out of a hundred is entirely misleading. Dr. Saunders’ attention-grabbing results were what gave the BTI report salience, providing an intellectual platform for the backfire narrative that Mr. Nordhaus and Mr. Shellenberger have since developed at BTI. Without Dr. Saunders’ results the 2011 report would not have been nearly as interesting to the outside world.

Second, it’s not at all clear whether Mr. Jenkins and Mr. Nordhaus stand by the work of their BTI colleague, Dr. Saunders. For example, in his recent posts on Twitter, Mr. Jenkins never opined on the validity of Dr. Saunders’ results, focusing instead on a defense of the 2011 BTI report he authored primarily based on the other references and findings it contained. (Indeed, at times Mr. Jenkins now sounds less like his former BTI colleagues and more like his fellow academic researchers writing on energy efficiency and rebound.)

For his part, Mr. Nordhaus has not offered any specifics regarding Dr. Saunders’ work, other than to endorse Professor Sorrell’s comment and Mr. Jenkins’ tweets.

Perhaps Mr. Jenkins and Mr. Nordhaus wish to clarify their positions on Dr. Saunders’ conclusions. Is the validity of Dr. Saunders’ results relevant to evaluating the 2011 BTI report? If not, why not? And if (as Mr. Jenkins suggests) Dr. Saunders’ analysis isn’t material to the BTI report’s conclusions, why was it featured so heavily before it had been peer reviewed?

Argument #5: The Burden of Proof

Ultimately, the argument over how to adjudicate Dr. Saunders’ article and our response comes down a debate over who bears the burden of proof.

As Dr. Saunders put it:

Of course the analysis stands to be improved by further geographic decomposition for each sector. Even better, firm-by-firm, but … [the] burden of proof rests on any who claim further disaggregation would substantially change results.

Professor Sorrell struck a similar tone:

Saunder’s [sic] aim in setting out the various 'cautions and limitations’ is to “encourage researchers to find ways to overcome them if energy efficiency rebound is to be properly understood”. That is the spirit in which the issue should be approached - improving our understanding of a complex phenomenon through better data and empirical methods. Identifying problems with the energy price series can contribute to that. But only if followed through with a revised analysis that contributes to the growing evidence base. Not as a basis for reinforcing entrenched positions[.]

Both Dr. Saunders and Professor Sorrell get this one backwards. The scientific process is all about evidence. If the evidence turns out to be weak, good scientists revisit their conclusions and revise them accordingly. That standard is all the more important in the social sciences, where human behavior makes for messier data.

We’ve done our best to make a clear case showing how Dr. Saunders’ energy data are severely flawed. Insisting that we go a step further and fix those problems, despite the fact that we’ve identified a lack of primary data necessary to that fix, is asking too much. It is sufficient for us to show that the existing data cannot support the conclusions Dr. Saunders and his BTI colleagues draw. Others can, if they wish, attempt to remedy those problems—but that is neither our job nor a prerequisite for a valid critique.

If anything, Dr. Saunders had an obligation to proactively address the shortcomings we found in his data. As we mentioned in our previous post, we discussed our concerns about data quality with him and Mr. Jenkins over a private lunch in March 2011 and again in June 2011 at a Carnegie Mellon University technical workshop in Washington, DC (PDF slides available here). Yet Dr. Saunders’ published article contains no mention of these issues. Surely timing wasn’t the problem: Technological Forecasting & Social Change reports that the initial manuscript was received in December of 2011; Dr. Saunders later provided a revised manuscript in response to reviewer comments in November 2012, a year and a half after we alerted him to a serious problem. When a researcher forges ahead with an approach that is known to be problematic, he doesn’t have the right to ask his critics to re-do his work for him.

Rather than double down on conclusions not supported by the data, Dr. Saunders and his colleagues should acknowledge the flaws in his analysis and cease relying on it to support any propositions about the rebound effect.

Conclusions

Our critics do not offer substantive defenses of Dr. Saunders’ analytical errors, nor can they explain away the Breakthrough Institute’s rhetorical overreaches in promoting them.

Documenting these problems does not tell us what the true magnitude of the rebound effect is, but it nevertheless offers reason to look elsewhere for that answer in the future. As we made clear in our journal article and earlier blog post, our work doesn’t attempt to estimate the likely range of rebound effects. Instead, we recommended several academic reviews from balanced and well-respected researchers at UC Berkeley, UC Davis, Yale, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Environmental Defense Fund. (Professor Sorrell’s 2007 UKERC review is another useful resource, though we expect he would agree that more contemporary assessments have captured additional studies published in the last ten years.)

In the end, credibility matters in this debate because energy efficiency research requires attention to detail, consistency between empirical evidence and theoretical modeling, and above all a commitment to intellectual integrity. We are sure that researchers like Dr. Saunders, Professor Sorrell, and Mr. Jenkins share these values, although we are equally confident that (1) the evidence does not support Dr. Saunders’ findings and (2) the 2011 BTI report from Mr. Jenkins, Mr. Nordhaus, and Mr. Shellenberger prematurely promoted Dr. Saunders’ results.

Finally, although we don’t seem to find much common ground on the technical issues, we appreciate the collegiality that Dr. Saunders, Mr. Jenkins, and Professor Sorrell have maintained throughout our discussions. It’s easy to let things get out of hand when arguing over contentious policy issues, and we are glad that this group is committed (as are we) to keeping the debate substantive and professional.

Corrigendum

*Our original post stated that Professor Sorrell is a Senior Fellow at Breakthrough Institute. However, Dr. Saunders informs us that Professor Sorrell is not and has never been formally affiliated with BTI. We regret the error and apologize for any confusion.

References

[1] Jorgenson, D., M. Ho, K. Stiroh (2005). Productivity (Volume 3): Information Technology and the American Growth Resurgence. Cambridge, M.A.: The MIT Press (see Table 4-4 on pp. 116-17).

[2] Oil prices are refiner acquisition costs for imported oil (1968 to 2014) and domestic first purchaser prices (1960 to 2014) from Table 9.1 of EIA’s Monthly Energy Review (December 2015). Natural gas wellhead prices (1960 to 2014) are from Table 9.10 in the same source. . Natural gas prices converted from $/cubic foot to $/mmBtu assuming 1029 Btu/cubic foot. Oil prices converted from $/bbl to $/mmBtu using 5.8 mmBtu/bbl.

[3] Although it is not relevant for the period of Dr. Saunders’ study, a similar episode occurred more recently with high world oil prices and abundant (but physically stranded) North American natural gas resources due to fracking. A separate and potentially more relevant episode concerns the domestic natural gas market. The gas market experienced significant regulatory changes over the long period of Dr. Saunders’ study, although the effects are not visible in the simple metric of price ratios we have chosen for the figure. Briefly, natural gas wholesale prices were federally regulated until the mid-1970s, with reforms eventually leading over the next decade or so to market-based wholesale prices based on regulated open-access interstate pipeline networks. During this time, wholesale consumers who signed long-term contracts at regulated prices faced significantly different prices than those who bought wholesale natural gas at market rates. Thus, the marginal price of natural gas industrial consumers experienced varied much more widely than a national average price would suggest.