Everyone makes mistakes on the rebound

What follows is a joint blog post by Danny Cullenward and Jonathan G. Koomey. To freely download the journal article in which we dissect the Saunders article on rebound, click here. Our article will be freely downloadable until January 20, 2016.

________________________________________________________________

Summary: About once a decade, a slew of popular headlines wrongly claim that energy efficiency doesn’t actually save energy or reduce emissions due to the rebound effect. We describe a recent episode in which headline-grabbing but fatally flawed claims on rebound misled policymakers and researchers.

________________________________________________________________

In February 2011, Jesse Jenkins, Ted Nordhaus, and Michael Shellenberger of the Breakthrough Institute released a widely read report reviewing the academic literature on energy efficiency and the rebound effect. And what, you might ask, is the rebound effect? As the authors put it:

Economists … have long observed that increasing the efficient production and consumption of energy drives a rebound in demand for energy and energy services, potentially resulting in a greater, not less, consumption of energy …. This is known in the energy economics literature as energy demand ‘rebound’ or, when rebound is greater than the initial energy savings, as ‘backfire.’[1]

The big issue here is the extent to which energy efficiency technologies and policies actually reduce energy consumption (and thereby avoid CO2 emissions). If policymakers fail to properly account for rebound effects, they will overestimate the contribution of energy efficiency in their climate strategies—a potentially critical shortcoming, as most climate mitigation efforts rely heavily on energy efficiency in both the developed and developing world.

Given the stakes, it should come as no surprise that a well-written popular literature review on this subject was poised to make headlines (e.g., in The New York Times, Nature, Huffington Post, and Conservation Magazine). All the more so, since the Breakthrough Report made an ostensibly strong case for backfire—the outcome in which efficiency actually causes greater consumption:

This review surveys the literature on rebound and backfire and considers the implications of these effects for climate change mitigation policy…. Rebound effects are real and significant, and combine to drive a total, economy-wide rebound in energy demand with the potential to erode much (and in some cases all) of the reductions in energy consumption expected to arise from below-cost energy efficiency improvements.[2]

In an accompanying blog post, the report’s authors claimed that the “expert consensus and empirical evidence that energy efficiency causes large rebounds and backfire is mostly unknown in the United States,” suggesting that energy efficiency advocates like Amory Lovins have “major media personalities” that block the truth from coming to light. And the truth, Mr. Jenkins wrote, is a sobering thing:

For every two steps forward we take with below cost energy efficiency, rebound effects mean we take one or two steps backwards, sometimes enough to completely erode the initial gains.

On the occasion of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry being awarded to the inventors of high-efficiency LED lighting technology, Mr. Shellenberger and Mr. Nordhaus criticized the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for citing the energy efficiency savings this technology would bring. In a New York Times OpEd, they claimed that:

LED and other ultraefficient lighting technologies are unlikely to reduce global energy consumption or reduce carbon emissions.

This is the stuff of Malcom Gladwell and Freakonomics, not the dry world of academic symposia. According to the Breakthrough Institute, everything you thought you knew about energy efficiency is wrong—and not just wrong, but totally backwards!

A thumb on the scale

If one digs into the 2011 Breakthrough Report, however, it turns out that the support for high rebound and backfire comes not from a systematic survey of a vast set of papers that document these outcomes in practice, but rather from two much more limited sources. One was a set of theoretical modeling studies (i.e., computer exercises, not empirical evidence). The second and most important source was a then-unpublished working paper from Dr. Harry Saunders, a Senior Fellow at the Breakthrough Institute.

Dr. Saunders’ empirical study found high rebound effects and even backfire across multiple industries in the United States. As the Breakthrough Report noted:

While Saunders (2010) is still in review as this paper is written, it represents an important contribution to the study of rebound effects that fills a key void in analysis of rebound for producing sectors of the economy. The paper is therefore included in this review despite its pre publication status.[3]

Reasonable people can debate the merits of including non-peer reviewed work in an authoritative literature review,[4] but Saunders’ report wasn’t merely included in the Breakthrough Report—it was the very centerpiece.

In most literature reviews, individual paper results are reported in tables or figures and, where the insights or methods are particularly important, briefly discussed in the main text. In contrast, the Breakthrough Report cites Dr. Saunders’ paper 25 times across 17 pages, with several full-page discussions and a detailed reproduction of its complete results.[5] No other citation received anywhere near this level of attention.

When the Breakthrough Report was released in early 2011, we expressed concerns over its conclusions, because we harbored serious doubts about the data Dr. Saunders used. Over lunch in Oakland that March, we shared our concerns with Dr. Saunders and Mr. Jenkins (now a PhD student at MIT)—both of whom are unfailingly cordial and professional, despite our differences—but to no avail.

Dr. Saunders insisted his data were of the highest quality, repeatedly invoking the reputation and authority of Professor Dale Jorgenson, the prominent Harvard economist who developed the dataset Dr. Saunders used. But we knew that no primary data were available to provide insights into industry-level prices and consumption data going back to 1960 and were concerned that Dr. Saunders had not appreciated the limitations of his secondary source.

As the rebound debate picked up steam that summer, one of us (D.C.) spoke at a Carnegie Mellon University workshop on the rebound effectand specifically addressed these limitations before a group of energy efficiency experts, including Dr. Saunders and Mr. Jenkins. Neither there, nor at any time since, were they able to explain how their data source obtained regional, industry-level data necessary to estimate the rebound effect by industry over some forty plus years. Yet in the publicity blitz accompanying the Breakthrough Report, not a word was heard about the data quality at the core of Dr. Saunders’ featured results.

Publish first, then peer review

Eventually, Dr. Saunders’ paper was published in the journal Technological Forecasting & Social Change in 2013.[6] Now that his article is in the peer-reviewed literature, official scientific reviews—such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—must consider Dr. Saunders’ results, and therefore we felt compelled to formally document our findings. The same journal recently published our response article.[7]

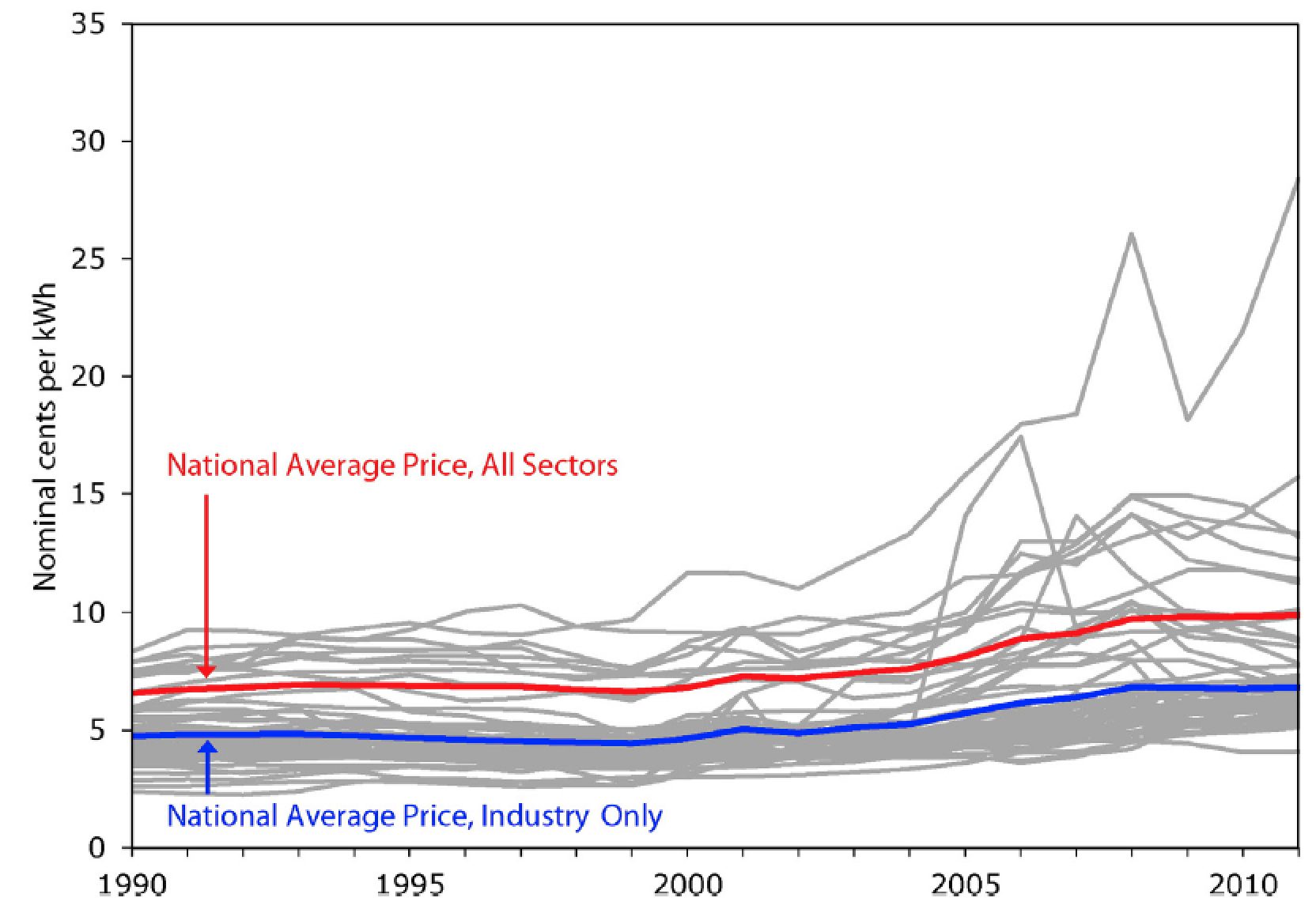

Our work confirms that Dr. Saunders’ data actually concern national average prices, not the sector- and location-specific marginal prices that energy economists agree are necessary to evaluate the rebound effect. The distinction is most important because actual energy prices vary widely by sector and location; in addition, economic theory asserts that changes in the marginal (not the average) price of energy services cause the rebound effect. As a result, Dr. Saunders’ findings of high rebound and backfire are wholly without support.

Fig. 8 from Cullenward and Koomey 2016. Industrial electricity prices by state (EIA data). This figure illustrates the variation in average annual electricity prices by state—this time, in the industrial sector. The fact that industrial prices are typically much lower than the average electricity price suggests that the use of national average prices significantly distorts the price signal facing most industrial customers. Each gray line represents the average annual price of electricity in one of the 50 states. The blue line is the average price for electricity in the industrial sector across the United States. The red line is the average price for electricity across all sectors in the United States. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) And yes, we know that it’s generally better to plot inflation adjusted prices, but because the underlying data in the Jorgenson data is in nominal dollars, we continue to use that convention in our article.

Lest this seem like a petty academic grievance, it’s as though Dr. Saunders set out to study the performance of individual NFL quarterbacks when their teams are behind in the third quarter of play, but did so using league-wide quarterback averages across entire games—not third-quarter statistics for each player. If that doesn’t sound credible to sports fans, trust us, it’s an even bigger problem when you’re talking about the last fifty years of U.S. economic history.

In addition, we showed how the data set Dr. Saunders used is an incompletely documented amalgamation of sources that are no longer publicly available. The U.S. government stopped publishing the primary sources that Professor Jorgenson originally used to create his data set; and on top of that, his reported energy prices are inconsistent with current government energy data. Professor Jorgenson’s efforts may reflect the best attempt to reconcile a messy historical record, but data of this quality must be carefully examined in secondary studies like Dr. Saunders’, not treated as a perfectly reliable primary source with several decimal points’ worth of precision.

Whatever one makes of the limitations of these data, it is important to note that the debate between experts—an admittedly dry process that might not interest many readers—occurred after the Breakthrough Institute represented Dr. Saunders’ results as the new gospel on rebound. This is the opposite of the way the scientific process is supposed to work. Even though we shared our concerns with Dr. Saunders in the spring and summer of 2011, he did not even mention them in his published paper, which he submitted for peer review that December.

As an all-too-common result, the normal mechanisms of peer review and expert feedback played a diminished role after the media blitz of a counter-intuitive narrative on energy efficiency took its toll.

Lessons for the future

Savvy readers won’t be surprised that bold claims on rebound and backfire led to impressive media coverage. In order to justify its position, however, the Breakthrough Institute relied on a then-unpublished working paper that purported to upend the expert consensus on energy efficiency. It is now clear that Dr. Saunders’ conclusions were based on a critically flawed analysis.

Avoiding similar problems in the future requires more engagement between the scientific community and journalists. In particular, science communicators need to take time to confirm they have a new angle on an old story. Like many other issues in environmental policy, the rebound effect has a long history, with debates flaring up every ten years or so.[8]It is entirely possible that new evidence emerges to challenge the conventional wisdom, but journalists should be skeptical of counterintuitive findings that haven’t been vetted within the relevant expert communities.

When a bold new idea is ready for prime time, we are confident its proponents will be able to point to clear and convincing empirical evidence that illustrates well-defined causal mechanisms behind the novel findings.

Nevertheless, in some cases, the academic peer review process may prove too slow to showcase truly exceptional and time-sensitive developments. In these uncommon instances journalists should be particularly careful with technical claims made outside of the peer review process, however, and seek critical views from experts within the scientific community to vet and then comment on any stories deemed credible by that community. We aren’t suggesting that scientists should have the exclusive right to talk about technically complex policy matters, but nor should groups other than those experts dominate the narrative on issues with a rich scientific history.

So what should readers make of the rebound effect? In our view, energy economists agree that (1) backfire is exceedingly rare, and (2) the rebound effect, while important in some cases, is unlikely to offset the majority of expected savings.[9]We also welcome more research on energy efficiency policy and the rebound effect, particularly in emerging economies, where the issue has received less attention thus far.

And while the Breakthrough Institute is right to criticize those who push policymakers to completely ignore the rebound effect, their argument that energy efficiency fails to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions is simply wrong. It’s time to move on.

About the authors

Danny Cullenward conducted this research during a Philomathia Research Fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught climate law and policy. An energy economist and lawyer by training, his work focuses on the design and implementation of science-based climate policy.

Jonathan Koomey is a Research Fellow at the Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance at Stanford University, worked for more than two decades at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and has been a visiting professor at Stanford, Yale, and UC Berkeley.

Notes

[1] Jesse Jenkins, Ted Nordhaus, and Michael Shellenberger, Energy Emergence: Rebound & Backfire as Emergent Phenomena. Breakthrough Institute Report (February 2011), page 4.

[2] Jenkins et al. (2011), page 4.

[3] Jenkins et al. (2011), page 16, footnote 13.

[4] Including within the Breakthrough Institute, it seems: BTI Senior Fellow Roger Pielke, Jr. strongly criticized the IPCC in 2009 for “laundering” non-peer reviewed findings into its high-profile climate science reports.

[5] We count citations by the number of paragraphs that specifically reference Dr. Saunders’ white paper, excluding multiple mentions within a single paragraph so as to conservatively assess its prominence in the Breakthrough Report. Dr. Saunders’ paper is discussed at length on pages 16-19 and 30-32, including a full page of results presented on page 18.

[6] Harry D. Saunders (2013), Historical evidence for energy efficiency rebound in 30 US sectors and a toolkit for rebound analysis. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 80(7): 1317-1330.

[7] Danny Cullenward and Jonathan G. Koomey (2016), A critique of Saunders’ ‘Historical evidence for energy efficiency rebound in 30 US sectors’, Technological Forecasting & Social Change 103: 203-213 (2016).

[8] See, for example, Daniel J. Khazzoom (1980), Economic implications for mandated efficiency in standards for household appliances. The Energy Journal 1: 21-40; John Henly, Henry Ruderman, and Mark D. Levine (1988), Energy Saving Resulting from the Adoption of More Efficient Appliances: A Follow-up. The Energy Journal 9(2): 163-170; Len Brookes (1990), The greenhouse effect: the fallacies in the energy efficiency solution. Energy Policy 18(2): 199-201; Lee Schipper (2000), On the rebound: the interaction of energy efficiency, energy use, and economic activity. Energy Policy 28(6-7): 351-353 (an entire special journal issue dedicated to the rebound effect); Steven Sorrell (2007), The Rebound Effect: an assessment of the evidence for economy-wide energy savings from improved energy efficiency. UK Energy Research Center Report.

[9] For a deeper treatment of the rebound issue, we recommend: Inês Azevedo (2014), Consumer End-Use Energy Efficiency and Rebound Effects. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 39: 393-418; Severin Borenstein (2015), A Microeconomic Framework for Evaluating Energy Efficiency Rebound And Some Implications. The Energy Journal36(1): 1-21; Kenneth Gillingham, David Rapson, and Gernot Wagner (2016), The rebound effect and energy efficiency policy. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, forthcoming.