Is natural gas the main driver of declines in coal generation in the US?

The US EIA Monthly Energy Review (Table 7.2a) includes data on net generation for the US (utilities plus independent generators), and from those data we can say something interesting about what was driving declines in coal generation from 2015 to 2016. The conventional wisdom is that cheap natural gas is the main driver of this decline, but that’s not true, at least in the 2015 to 2016 time frame.

I downloaded the data from the EIA web site, and converted the net generation numbers to billion kWh (equivalent to terawatt-hours) in my excel workbook. I then calculated the change from 2015 to 2016 and combined pumped storage hydroelectricity with conventional hydro.

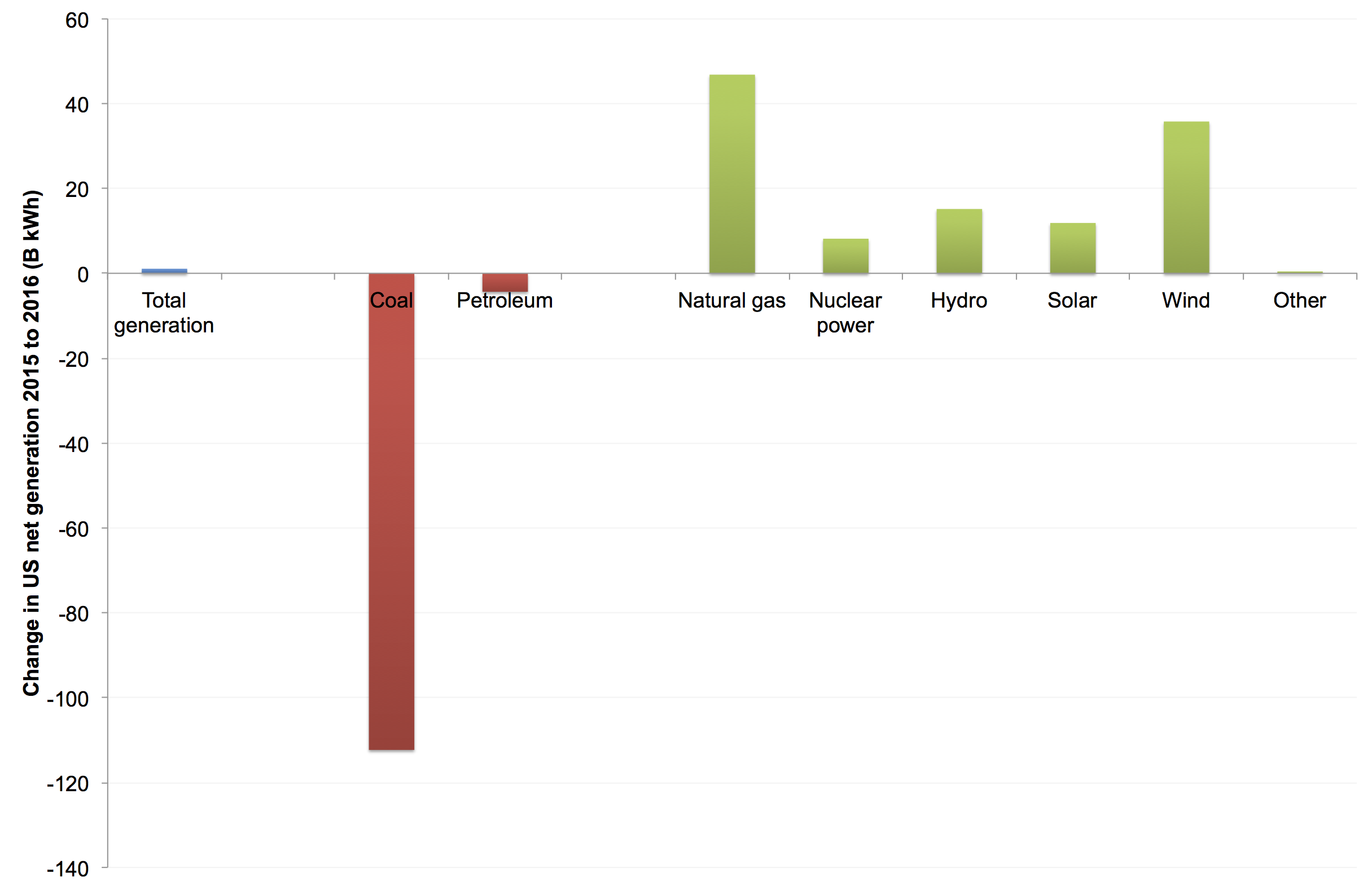

The net result is shown in the following figure:

The graph shows that natural gas was responsible for offsetting about 40% of the total decline in coal and petroleum generation, but that wind plus solar displaced about the same amount. So natural gas is an important part of the story, but the other alternatives (including nuclear and hydro) are in the aggregate more important. With the recent exponential increases in installed capacity of solar and wind, they are destined to become much more important in short order.

It is not clear to me whether the growth in rooftop solar generation is included in these numbers. I know that EIA has been working to get better data on that sector, but sometimes the data gears churn slowly. If you can answer that question, please contact me!

Another important factor not accounted for here is that net generation and electricity consumption in the US has been flat since 2007 (Hirsh and Koomey 2015), which indicates decoupling between electricity demand and GDP. In the years since the mid 1990s this decoupling has been pronounced, while from 1973 to the mid 1990s electricity consumption grew in lockstep with GDP.

GDP has grown about 2%/year on average since 2010, and if we apply that 2% to net generation in 2015 we can estimate that electricity demand is about 80 B kWh lower than it would have been without that decoupling. That shift in demand (which is a function of both efficiency and structural change) is bigger than any of the other single contributors to changes in generation in the figure. For more discussion of these issues, see Hirsh and Koomey 2015.

Reference

Hirsh, Richard F., and Jonathan G. Koomey. 2015. “Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth: A New Relationship with Significant Consequences?” The Electricity Journal. vol. 28, no. 9. November. pp. 72-84. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040619015002067]