The feasibility of meeting the 2 C warming limit

Dave Roberts of Vox recently posted an article about the climate problem titled “The awful truth about climate change no one wants to admit”, the point of which he summarizes as “barring miracles, humanity is in for some awful shit.” This conclusion is true even if we manage to keep warming to 2C or below, but even more true if we don’t.

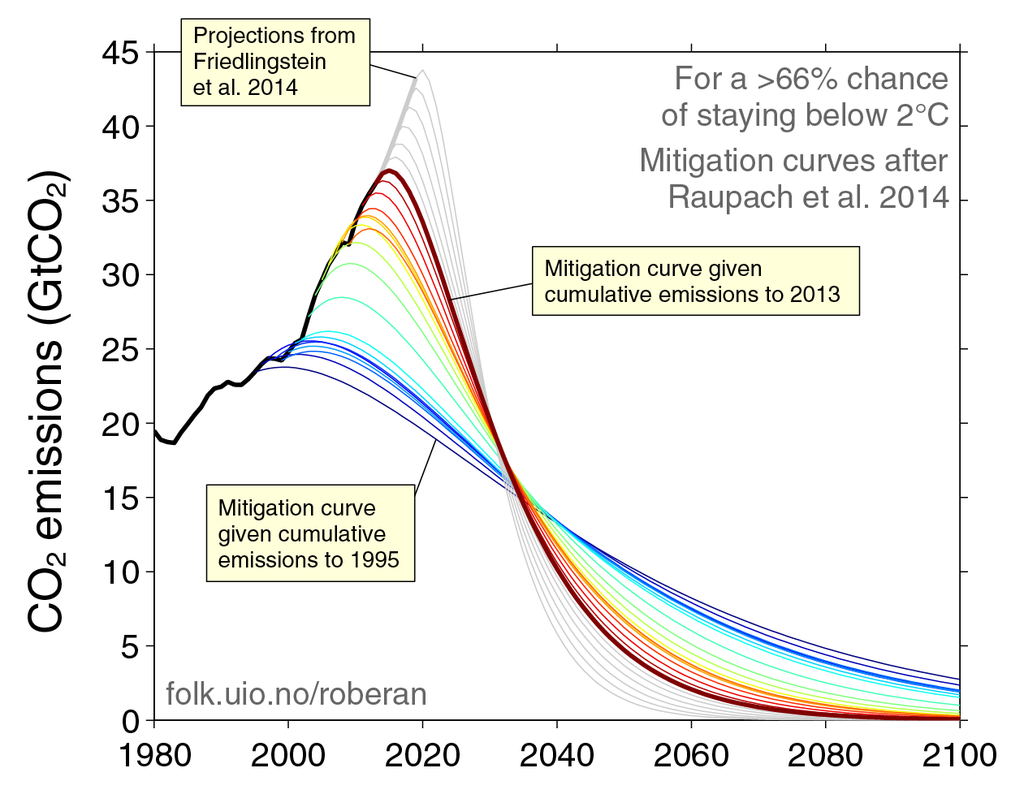

In support of this point of view, Roberts cites analysis showing the increasing difficulty of meeting the 2 C warming limit with every year of delay. This phenomenon is well known to people who understand the warming limit framing, but it can’t be repeated enough. Delay makes solving the problem more costly and difficult, a fact that is summarized in the graph below.

Source: Robbie Andrew

Unfortunately, this article falls prey to a particularly common pitfall, that of assuming that we can accurately assess feasibility decades hence. This mistake is particularly problematic for assessments of political feasibility, because political reality can be remade literally overnight by pivotal events.

Here’s how I summarized the problem in Cold Cash, Cool Climate: Science-based Advice for Ecological Entrepreneurs:

Analysts always impose their ideas of what is possible on which policies and technologies are analyzed, but as I’ll argue in the next chapter, with few exceptions it is very difficult to predict years in advance what is feasible and what isn’t. People also usually underestimate the rate and scope of change that can occur with determined effort, and this bias is reinforced by the use of models that ignore important effects (like increasing returns to scale and other sources of path dependence), and include rigidities that don’t exist in the real economy (like assuming that individual and institutional decision making will be just like that in the past, even in a future that is drastically different).[1] For all these reasons, it is a mistake to rely too heavily on models of economic systems to constrain our thinking about the future.

And it is not just the creators of complex economic models who fall prey to this pitfall. Rob Socolow, one of the pioneers of the wedges method, was quoted in an article looking back on the contribution of his efforts as saying “I said hundreds of times the world should be very pleased with itself if the amount of emissions was the same in 50 years as it is today.”[2] Now I’m a big fan of Rob, we’ve been colleagues for years, and I have great admiration for what the wedges papers contributed to advancing the climate debate. But this statement has always rubbed me the wrong way, and I finally figured out why: it imposes his informal judgment about what is feasible on the analysis of the problem, and as I discuss in the next chapter, that is almost impossible to determine in advance.

Feasibility depends on context, and on what we are willing to pay to minimize risks. What if there’s a big climate-related disaster and we finally decide that it’s a real emergency (like World War II)? In that case we’d make every effort to fix the problem, and what would be possible then is far beyond what we could imagine today. It is therefore a mistake for analysts to impose an informal feasibility judgment when considering a problem like this one, and instead we should aim for what we think is the best outcome from a risk minimization perspective, and if we don’t quite get there, then we’ll have to deal with the consequences. But if we aim too low, we might miss possibilities that we’d otherwise be able to capture.

Judging feasibility without careful analysis really is a distraction–people obsessed with what is possible politically or practically kill innovative thinking because they miss the many degrees of freedom that we have to shape the future. They take the system as it is for granted, and we just can’t do that anymore.

An archetypal example is the discussion about integrating intermittent renewable power generation (like wind generation or solar photovoltaics) into the grid. In the old days the grizzled utility guys would say things like “maybe you can have a few percent of those resources on the grid, but above that you’ll destabilize the system”. Now we know that’s nonsense, and the “conventional wisdom percentage” of what’s allowable has crept up over the years, but it always reflected a static (and incomplete) view of what the system could handle. Over time, we can even change the system to use smaller gas-fired power plants that respond more rapidly to changes in loads, install better grid controls, institute variable pricing using smart meters, use weather forecasting, and create better software for anticipating grid problems. All of those things together should allow us to handle much more intermittency than what a conventional utility operator might think is feasible. And as we become smarter about energy storage, things will get easier still.[3]

The same lesson applies to any attempts to envision a vastly different energy system than the one we have today. We need to take off our feasibility blinders and shoot for the lowest emissions systems we can create. That doesn’t mean we can ignore real constraints, but we do need to throw off the illusory ones that are an artifact of our limited foresight. And if we don’t quite make it, that’s life, but at least it won’t be for lack of trying.

Context matters, and what seems infeasible today based on judgments about political will can become feasible tomorrow. Who would have thought, for example, that Chinese coal use could drop 7.4% in a year? Happily, that’s just what happened in April 2015. Who would have thought that the US auto industry could retool from making millions of cars per year to building war machines in 6 months? Yet that’s what happened soon after the US entered World War II. In both cases, what seemed impossible looking forward became possible when people put their minds to it (and policy makers pushed for big changes)

I would rephrase Roberts’ summary to say “we can avoid some awful shit if we just get our act together, and the only thing standing in the way is our willingness to face the reality of the climate problem.” Whether we can meet the 2 C warming limit is something that cannot be accurately predicted in advance, it can only be determined by making the attempt. Modeling exercises can be useful, but it is only by trying to reduce emissions that we can determine what is possible.

Our choices today affect our options tomorrow. If we choose wisely, we can still avoid the worst consequences of climate change, but we must choose. We are out of time, and the time for choice is now.

References

[1] Koomey, Jonathan. 2002. "From My Perspective: Avoiding "The Big Mistake” in Forecasting Technology Adoption.“ Technological Forecasting and Social Change. vol. 69, no. 5. June. pp. 511-518.

[2] Struck, Doug. 2011. "Climate Scientist Fears His ‘Wedges’ Made It Seem Too Easy.” In National Geographic. May 17. [Read online at http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2011/05/110517-global-warming-scientist-concern/]

[3] See the recently commissioned Gemasolar plant in Spain for one way to address the storage issue, using molten salt heat storage [http://www.nrel.gov/csp/solarpaces/project_detail.cfm/projectID=40]. There are many other ways, some based on long proven technologies (like pumped storage, flywheels, compressed air, or batteries) and others that are more exotic, like molten salts.